Oct. 27, 2022

The intensively researched origins of The Sleeping Car Porter

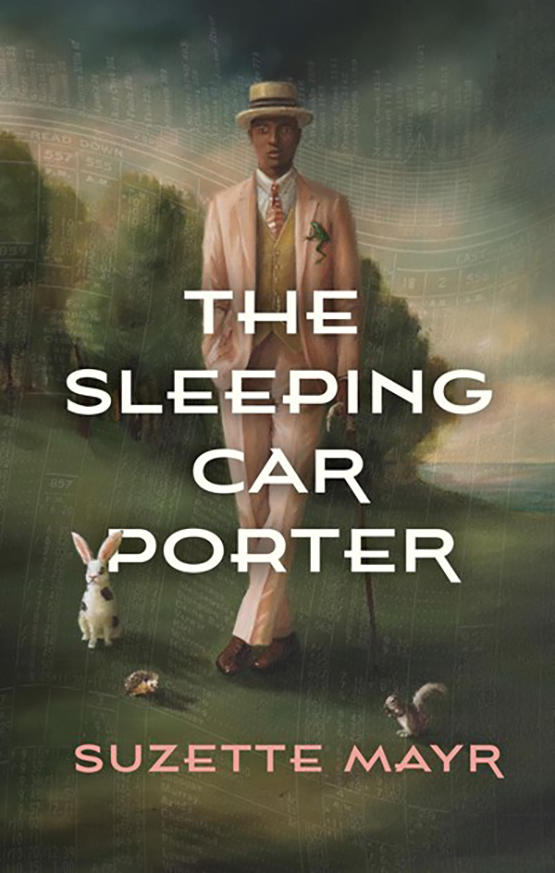

UPDATE NOV. 8, 2022: Dr. Suzette Mayr has been named the winner of the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize for her novel, The Sleeping Car Porter. The announcement was made at a black-tie dinner and award ceremony in Toronto last night. The Scotiabank Giller Prize is the most prestigious literary prize in Canada, recognizing excellence in Canadian fiction. The following article was first published on Oct. 27, 2022.

The evolution of Suzette Mayr’s The Sleeping Car Porter (2022) isn’t just a story of extraordinary creative inspiration, though its tale of a gay, Black sleeping car porter on a 1929 passenger train from Montreal to Calgary, which becomes stalled for two days thanks to a mudslide in Banff, is certainly an inspired premise.

The fact that it was shortlisted for, and has now won Canada’s top literary award, The Scotiabank Giller Prize, speaks to the richness of its vision.

But the novel’s origins are also steeped in a staggering amount of research that began nearly two decades from the initial spark of an idea, which has seen Dr. Mayr, BA'90, PhD, a professor of creative writing in the Department of English at the University of Calgary, taking on the work of historian, detective, investigative journalist, and cultural anthropologist.

This intensive preparation for the novel, Mayr’s sixth, has taken her from Cranbrook and Winnipeg to Montreal and New York City, among the stops at a myriad of museums, libraries, railway stations, and archives.

“It was a long path and a ton of research along the way,” Mayr says. “I was so nervous about getting the details right, and it took years.”

Mayr sought to understand the lives of Black and gay men in the 1920s, a particularly difficult task where the latter was concerned, as so many gay men of the era were closeted. She also delved deep into the cultural mores of the times, with an emphasis on railway culture and the era’s unsung sleeping car porters.

The book had a “very bumpy genesis,” says Mayr, originating 19 years ago from a conversation with celebrated poet Fred Wah, who had been her creative writing professor at the University of Calgary. Wah made an offhanded remark that Mayr should write a book about sleeping car porters.

“I wasn’t even sure what to do with that, but I always I like to have projects on the back burner, so I thought ‘Why not?’” she recalls. “But I wasn’t mature enough as a writer to handle the topic at the time. I certainly didn’t know anything about historical research.”

Professor Suzette Mayr poses with the Scotiabank Giller Prize after the announcement in Toronto on Nov. 7, 2022.

Ryan Emberley Photography

Researching the lives of sleeping car porters was a true challenge because so little had been written about them. “It was working-class history, so it wasn’t considered important,” says Mayr. “I was so naïve. Did people have running water in their homes? Did they have light bulbs then? I really had no idea.”

Searching for answers, Mayr went on the hunt for photos of the interiors of working-class homes from the era. “There weren’t any I could find, because the only photos in the archives were from the homes of rich people,” she says.

“I was talking to an archivist in Winnipeg, and he mentioned they did have photos from the inside of working-class homes, but they were crime scene photos. I’d be looking at these photos going ‘Aha! There is a light bulb hanging from that ceiling! Oh, and there’s a dead body in the corner of the room.”

She adds: “I followed some wild paths to find what I needed. What was disorienting about the historical research was that there were no books on what I wanted. It was more a matter of finding a footnote in a book and then chasing it down, or finding an old postcard and taking it from one archivist to another.”

Mayr’s research hit its stride in 2013, thanks to a SSHRC Insight Grant which gave her the means “to do some serious digging,” travelling to museums and archives all over North America, with the aid of a hired research assistant.

Slowly, the pieces came together, helping Mayr shape her story. An old article on how Canadian railway companies actively recruited in the Caribbean added one piece to the puzzle. Another article focused on the criminal record of a white man who was caught engaging in sexual activity with a Black sleeping car porter. One more building block for the story.

But the novel’s inspirations weren’t purely historical. A 2012 mudslide in Banff, which shut down the Trans-Canada Highway, also provided inspiration.

“When I was putting the plot points together, I thought about where the drama would come from. In 2018, I read about a train that was delayed for 45 hours in a separate incident,” says Mayr. “Now that would be a hard ride. Right then I knew, my sleeping car porter’s train was going to be delayed by a mudslide in the Rocky Mountains.”

While The Sleeping Car Porter has been, by far, the most research intensive of all Mayr’s novels, she points out that they’ve all involved copious research.

For The Widows (1998), about elderly German immigrant women determined to plunge over Niagara Falls in a barrel, she found herself researching Niagara Falls and the stories of real people who had taken the plunge. She also delved into the psychology of German women who came of age during the Second World War.

For Monoceros (2011), which revolved around the suicide of a bullied teen, she did a deep dive into interviews with and memoirs by parents of children who had died by suicide.

“There’s always research to do,” Mayr says. “If you do your job well as a writer, nobody knows you’ve done all this research, because the work reads effortlessly,” she says. “You don’t want the research to show, because if you do, the book won’t work. So, you basically hide it.”

“People tend to think that with writers, the work comes only from a place of creative inspiration, and yes, imagination is a big part of that. But I think people would be surprised by the abundance of research that feeds a novel and builds its foundation.”

Suzette Mayr is the winner of the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize. Learn more